This past summer, we planned to take the family to Disney World while the kids were still young enough to feel the magic and old enough to remember it. But with the political climate being what it is, and as a Hispanic family, the idea of crossing the border felt like tempting fate. We didn’t want to risk the trip and end up deported to Tijuana, or is it El Salvador now?

So, we decided instead of visiting Disney, to explore our great big country, Canada. We’ve been here for decades, and we haven’t seen much of it, which is a shame because it’s a beautiful country. We could either go West or East, and we chose East, because it was closest and cheapest. So, we packed our bags and our kids into our minivan and drove the 790 km (or 490 miles, for any US folks reading this). It’s a two-day ride stopping in Fredericton, New Brunswick, for the night.

Arriving in Halifax, I had a whole itinerary planned, and one of the main stops was visiting the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. One of the main attractions there is the Titanic Exhibit. They have many replicas of the boat or its parts, as well as several authentic items. You can stop and read firsthand testimonials of crew members and passengers who survived. Accounts of the crew members of the RMS Carpathia, the first ship to reach the survivors of the Titanic, or the CS Mackay-Bennett, the ship tasked with recovering the bodies from the cold seas, are especially poignant.

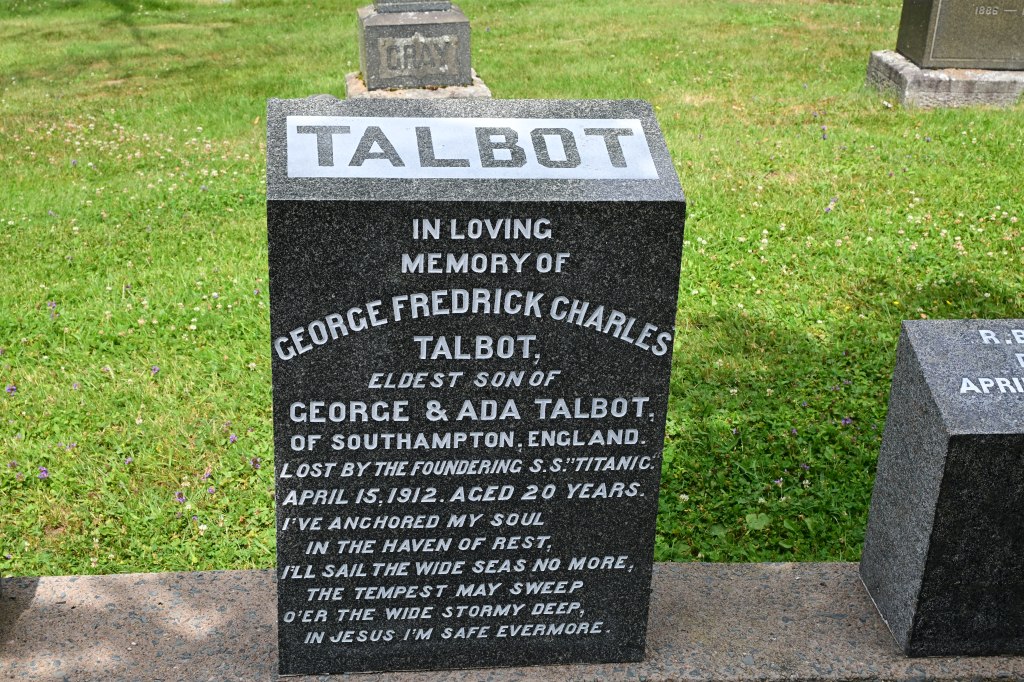

It’s a small exhibit, but a significant one considering that Halifax is the city where several of the retrieved bodies are still buried to this day. Visiting the cemetery that is now their eternal resting place, the Fairview Lawn Cemetery, is another must if you’re ever in Halifax. Sadly, several of the people buried there were never identified, or their bodies were never claimed by any relatives. You can find crew members, men, women, and even children. On the children’s tombstones, visitors have placed toys. My children left toys as well, touched that someone so young was buried there.

The tombstones are placed in such a way that they form the bow of a ship. You can either visit on your own or have a guided tour. There are 121 souls buried in the Fairview Lawn Cemetery; many of the graves are marked with the single word “Unknown,” along with a number indicating the order in which they were recovered. Sadly, the crew of the CS Mackay-Bennett didn’t arrive on site until several days after the tragedy. By that time, many bodies were badly decomposed, despite the frigid waters, and beyond recognition. Also, their priorities were in identifying the first-class passengers first. Arguably, the most valuable passengers at the time, and therefore, many of the “Unknown” graves are most likely those of third-class passengers.

I left the cemetery with a heavy heart for all those men, women, and children who were never claimed, never identified, never made it home.

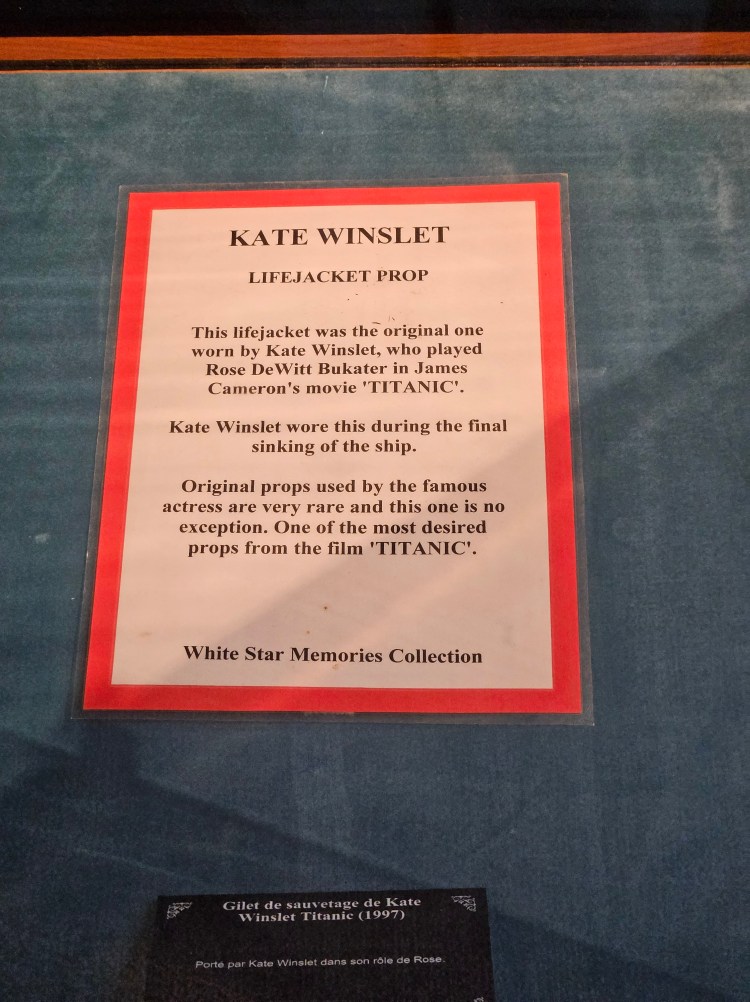

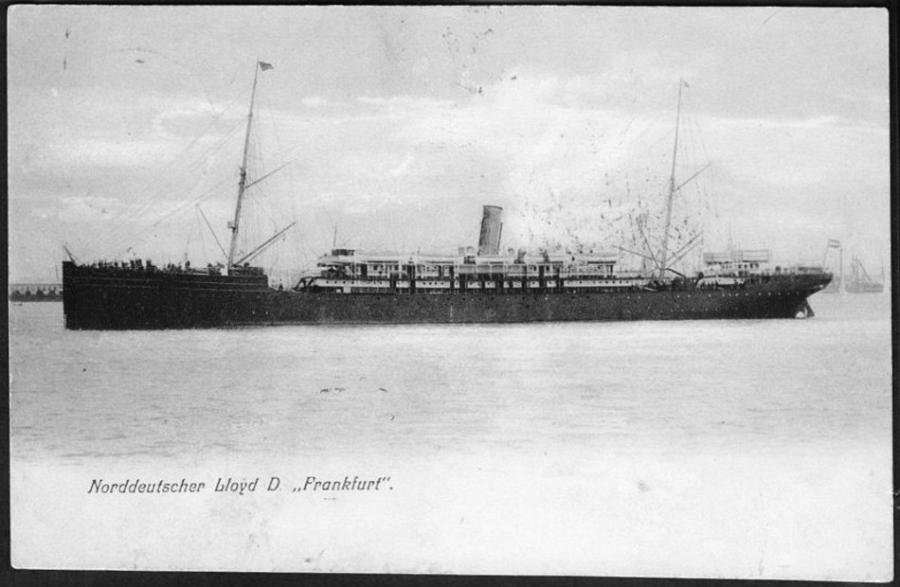

Several months later, back home in Montreal, I saw that a new Titanic Exhibit was coming to town. This exhibit was different in that it was an immersive experience. Divided between reality and fiction, it included several props from the James Cameron movie. It contained information that the Halifax one didn’t. Like the Morse code exchanges between the RMS Titanic as it was sinking and several other ships that fateful night. One of the very first ships to answer the Titanic’s distress call was the German steamer Frankfurt. That ship was at 153 nautical miles from the sinking Titanic (282 km or 175 miles). The Titanic’s senior wireless operator, Jack Phillips, famously answered the Frankfurt to “Keep out…You fool!” because he knew the ship was a lifetime away. He was under so much stress and inundated by messages from other ships that had also answered the Titanic’s SOS.

Still, with a patchy reception and not much to go on, the captain of the Frankfurt decided to turn her around and head full steam ahead to the coordinates of the Titanic. They arrived roughly 12 hours later to an empty see, wreckage and floating bodies. The Carpathia had already rescued all of the survivors. And she wasn’t the only one. Many ships that night answered Titanic’s call for help, and many arrived at the site to find they had arrived too late. It’s a testament to the solidarity of the ships at sea at the time. Even knowing they were almost certainly too far away, many ships answered the call and did not hesitate to act. They all kept their wireless operator listening and on standby in the hopes that the Titanic would show a sign of life. They all headed into a dangerous part of the Atlantic known for icebergs, full steam ahead in the dim hope that they might save someone.

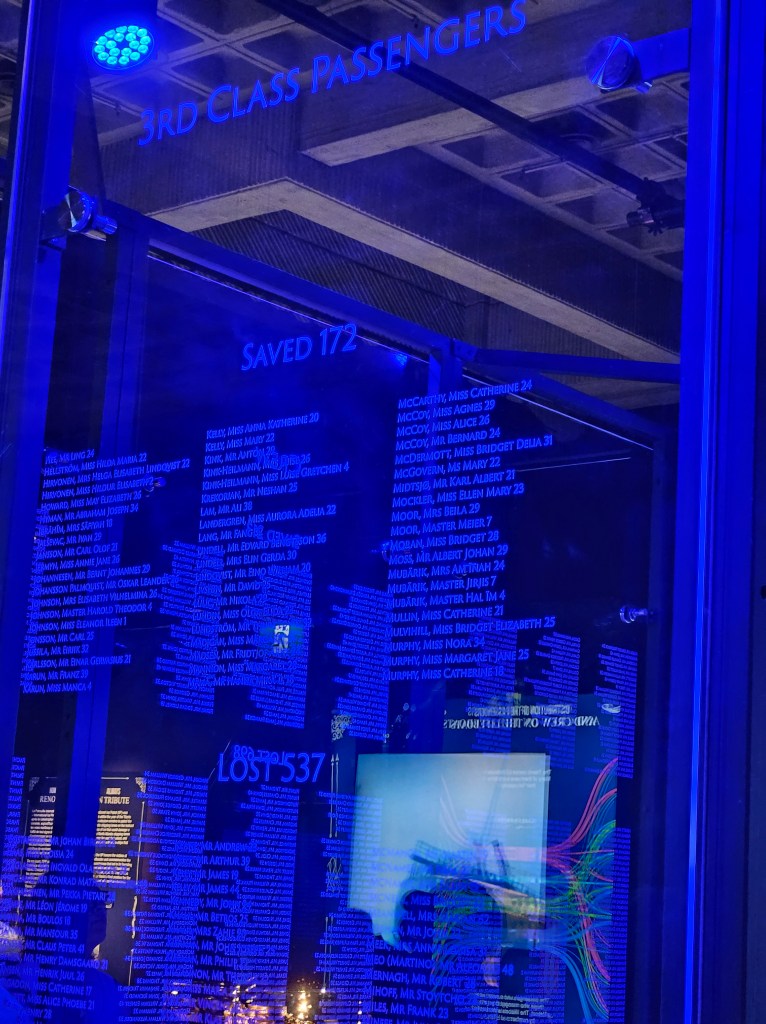

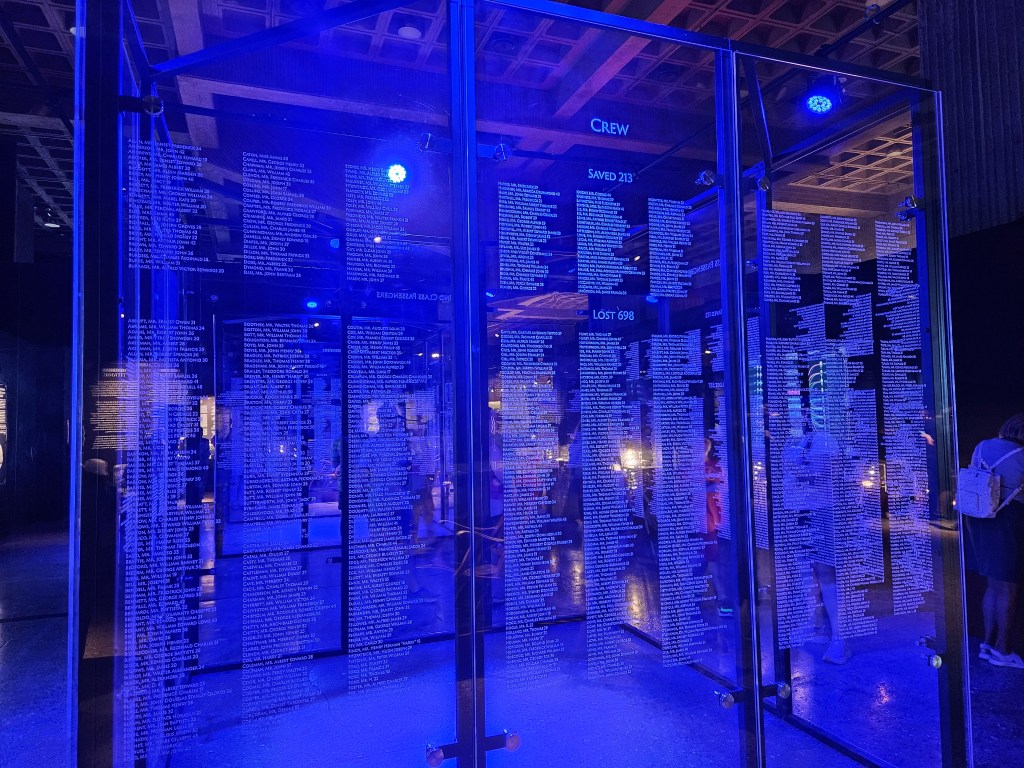

At the end of the exhibit, on clear plastic panels, are the classes and names of all the people who died that night. Comparing the victims between them, the first class passengers mainly had men die. Middle-aged men mostly. In the second class, you see that mostly men died as well, but also a few more women. Arriving at the panel of the third class passengers, your heart can’t help but sink at all the names. Almost all 709 third-class passengers died. Only 172 were saved. That’s barely 25%. In contrast, the first class passengers had a 62% survival rate.

One of the things that is painfully obvious on the third-class panel is the number of children that didn’t make it. Entire families were decimated, and James Cameron’s movie depicts those reasons in vivid detail. Several crew members didn’t open the gates to allow the third-class passengers to reach the upper deck. Several were foreigners who didn’t speak English and didn’t understand the crew members’ instructions. Several lost their way in the labyrinth of the lower levels, not knowing how to read the signs in the halls indicating how to reach the upper levels to save themselves. For those who managed to get to the upper deck, it was too late. They ran out of time. In one of the most unforgivable decisions in maritime history, the White Star Line sent Titanic to sea without enough lifeboats for all her passengers. The reason being: they would obstruct the view of the first-class passengers, and they were deemed unnecessary on a ship that was supposed to be unsinkable.

Reading through the names of the third-class victims, two families stood out to me: the Skoogs and the Rices. Large families with many children. After a bit of research, this is what I found about them:

The Skoog Family

Wilhelm Johansson Skoog (40) and Anna Bernhardina Skoog (43) boarded the Titanic in Southampton with their children Karl Thorsten (11), Mabel (9), Harald (5), and Margit Elizabeth (2).

The Skoogs were emigrating from Finland to start a new life in America. They had lived in Sweden for a time before deciding to make the journey overseas, booking third-class passage on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. The family was last seen together below decks after the collision, reportedly trying to make their way toward the forward companionways. The ship’s complex layout and the chaos of the night made escape for third-class passengers especially difficult. No member of the Skoog family survived, and their story comes only from fellow passengers who remembered seeing them that night.

The Rice Family

Margaret Rice (39) was a widow from Athlone, Ireland. Her husband, William, had died in a railway accident, leaving her to raise their five sons alone: Albert (10), George Hugh (8), Eric (7), Arthur (4), and Eugene Francis (2).

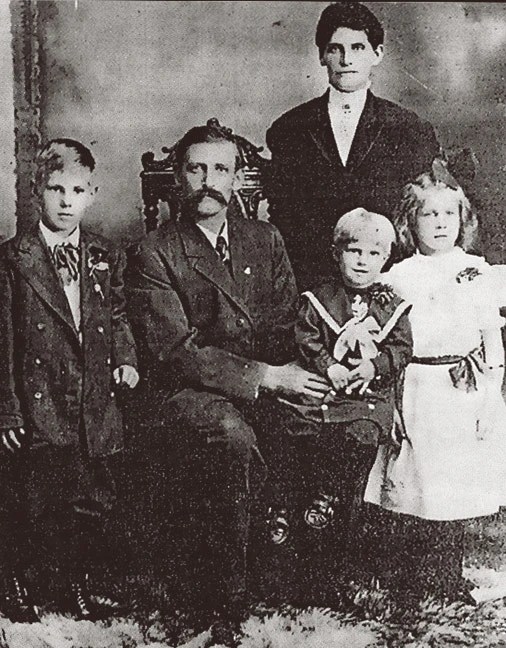

This is the only known photo of the entire Rice family together. All six sailed third class on the Titanic. None survived.

Margaret decided to emigrate to Spokane, Washington, where her brother had settled. She booked passage on the Titanic at Queenstown (now Cobh) in third class. Survivors recalled seeing her holding her youngest, Eugene, during the sinking, with her other sons clustered around her. As the Titanic’s bow went under, she was reportedly seen moving toward the stern, possibly in search of a way to the boats. None of the Rice family survived.

And there are countless more stories like those. As you make your way through the exhibit, it’s painfully apparent to us now, 113 years later, the awful mistakes made that night by the captain and crew. And still so many questions left unanswered. On the day the Titanic sank, the ship received many warnings from other ships about icebergs present in the area. The captain of the Titanic, Captain Edward John Smith, was notified several times of those messages. However, he still didn’t slow down the ship. The ship was navigating full steam ahead.

First-class passengers paid the wireless operators to send personal messages to family members, so instead of focusing on the warnings from other ships, they were busy sending greetings from wealthy passengers. Why was this allowed?

And finally, countless people complain that many ships sank before and after the Titanic with many more losses of life, so why the obsession? And I have no clear answer. But maybe because it was her maiden voyage, perhaps because it was her captain’s last voyage. Maybe because the mere fact that she was deemed unsinkable is a symbol of Men’s untamed arrogance and defiance towards nature, and how easy it is for her to remind us that we are at her mercy.

Titanic’s story will live on, I imagine long after we are gone, as a reminder that we are only here by God’s good graces, and that human nature is not infallible, but that in our hour of need, instead of only looking towards the heavens for salvation, we look to those around us, because many people tried that night to save as many as they could; as the panel of the crew members who died that night can testify. Apart from the captain, his senior wireless operator, several officers and other crew members, the entire engineering team sank with the ship that night. True to their post, working the engines and electrical circuits to try and keep the Titanic’s lights on for as long as possible. Many eye-witness accounts report the ship was still completely illuminated as the dark waters engulfed it.

One thing is for sure: as you stare at all the crew members who died that night trying to save passengers, you walk out of there with a deeper level of respect for those who roam the seas, and for the risks they take so that others may live.

And maybe, for them, we can turn to the Man upstairs once in a while and pray:

O hear us when we cry to Thee, For those in peril on the sea.